In November 1989 the World Meteorological Organization WMO and UN Environment Programme UNEP established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IPCC. The IPCC is the internationally accepted authority on climate change and is composed of thousands of scientists and other experts who contribute on a voluntary basis. The role of the IPCC is to provide the world with an objective, scientific view of climate change and its political and economic impacts. The IPCC reports have the agreement of climate scientists globally and the consensus of more than 120 participating governments.

The IPCC has published five comprehensive assessment reports reviewing the latest climate science, as well as a number of special reports on particular topics.

The IPCC published its First Assessment Report (FAR) in 1990, a supplementary report in 1992, a Second Assessment Report (SAR) in 1995, a Third Assessment Report (TAR) in 2001, a Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) in 2007 and a Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) in 2014.

In November 1990 The IPCC’s first assessment report stated that ‘emissions resulting from human activities are substantially increasing the atmospheric concentrations of the greenhouse gases: CO2, methane, CFCs and nitrous oxide. These increases will enhance the greenhouse effect, resulting on average in an additional warming of the Earth’s surface.

The 1992 supplementary report was an update, requested following the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in June of that year. The IPCC concluded that research since 1990 did “not affect our fundamental understanding of the science of the greenhouse effect and either confirm or do not justify alteration of the major conclusions of the first IPCC scientific assessment”.

The 1995 IPCC report estimated that a doubling of CO2, which was expected to come around the middle of the 21st century, would raise the average global temperature somewhere between 1.5 and 4.5°C. That was exactly the range of numbers announced by important groups one after another ever since 1979, when a committee of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences had published 3°C plus or minus 1.5°C as a plausible guess.

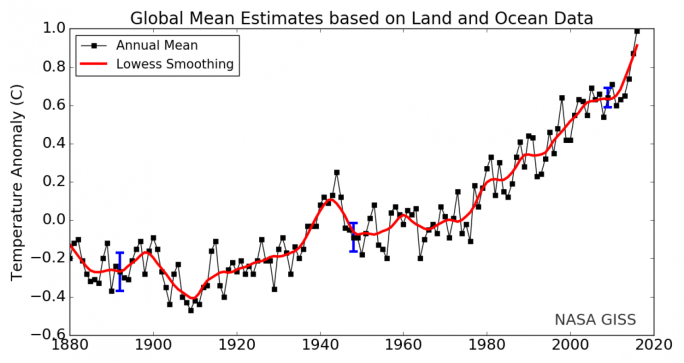

The third report of the IPCC, issued in 2001, bluntly concluded that the world was rapidly getting warmer. Further, strong new evidence showed that ‘most of the observed warming over the last 50 years is likely to have been due to the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations.’ Computer modelling had improved to the point where the panel could confidently state that the rate of warming was ‘very likely to be without precedent during at least the last 10,000 years.’ Further, the range of warming that the IPCC predicted for the late 21st century now ran from 1.4°C up to 5.8°C. China’s rapid industrialisation had led to an upward revision of predictions and this range was not for the traditional doubled CO2 level, which was now expected to arrive around mid-century, but for the still higher levels that would come after 2070 unless the world took action.

In February 2005, the Kyoto Protocol came into effect with 141 signatory nations, including all the major industrial nations except the US. The protocol established legally binding obligations for developed countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in the period 2008–2012.

The Fourth IPCC report published in 2007 saw most of the world’s climate scientists contributing to shaping its conclusions. Computer modellers worked to produce more accurate global warming results specifically for the report. The range of temperatures predicted for the end of the century had not changed much since the 2001 report. Their best guess was still roughly 3°C of warming, but they had grown more certain that we were very unlikely to get away with a rise of less than 1.5°C. The computer models did not agree so well on the upper limit — there was a small possibility that global temperature could soar to 6°C or even higher. That possibility increased if, contrary to the IPCC’s baseline assumption, the world continued with business-as-usual instead of severely restraining its emissions.

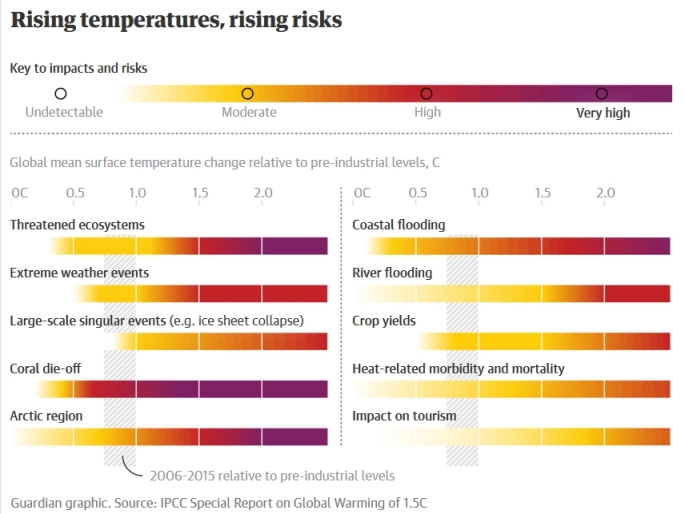

The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancún, Mexico, recognised that ‘climate change represents an urgent and potentially irreversible threat to human societies and the planet, which needs to be urgently addressed by all parties’. It produced an agreement that deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions were required to hold the increase in global average temperature below 2°C above pre-industrial levels (computer studies tended to show that serious effects for life on earth would begin to appear above 1.5°C). The agreement also notes that addressing climate change requires a paradigm shift towards building a low-carbon society.

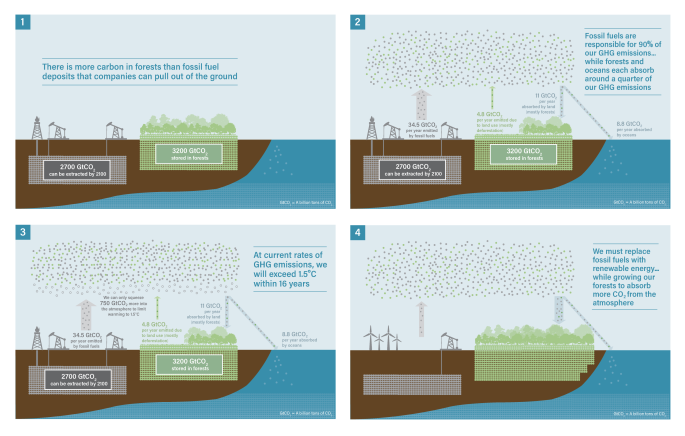

On May 9, 2013, atmospheric CO2 levels surpassed 400 ppm (parts per million) for the first time in recorded history. This recent relentless rise in CO2 shows a remarkably constant relationship with fossil-fuel burning.

The Fifth IPCC Assessment Report was finalised in 2014. The principal findings were:

- Warming of the atmosphere and ocean system is unequivocal. Many of the associated impacts such as sea level change (among other metrics) have occurred since 1950 at rates unprecedented in the historical record.

- There is a clear human influence on the climate

It also projected that:

- Further warming will continue if emissions of greenhouse gases continue.

- The global surface temperature increase by the end of the 21st century is likely to exceed 1.5 °C relative to the 1850 to 1900 period for most scenarios, and is likely to exceed 2.0 °C for many scenarios

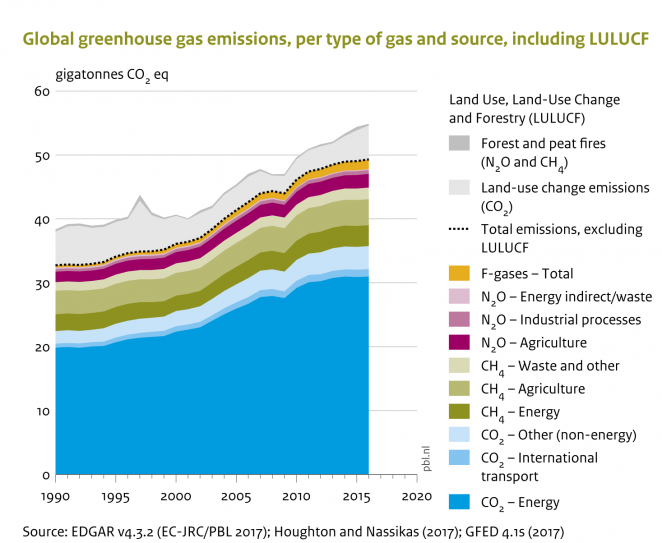

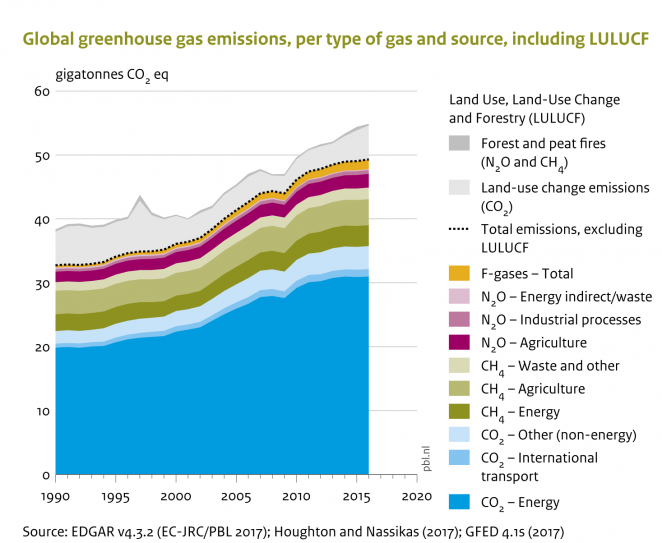

Global emissions of greenhouses gases, however, continued to increase. In 2014, the 400 ppm mark of CO2 in the atmosphere was passed in March. The average CO2 concentrations for March, April and June 2014 were all above 400 ppm, the first time that has been recorded. This is a large increase from pre-industrial CO2 concentrations, which were around 280 ppm. These high CO2 levels have not been seen on Earth in somewhere between 800,000 and 15 million years . If fossil-fuel burning continues at a business-as-usual rate – such that humanity exhausts the current oil, gas and coal reserves over the next few centuries – CO2 will continue to rise to levels of order of 1500 ppm. The atmosphere would then not return to pre-industrial levels even tens of thousands of years into the future.

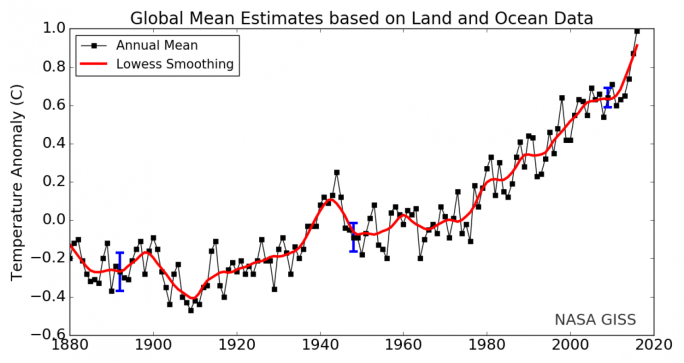

In 2015 The Scripps Institution of Oceanography recorded atmospheric CO2 levels of above 400 ppm on the first day of the year, followed by January 03 and January 07. The levels of global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise as do global temperatures (see graphs below).

The sixth IPCC report is due in 2022.

The IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C was published on 8 October 2018.